2021 AFPM Annual Meeting Virtual Edition: Adapting for competitive advantage

ROGAN JONES, Vice President of Sales and Co-Founder, and RICK KAISER, Product Manager for Software Solutions, AIS Software

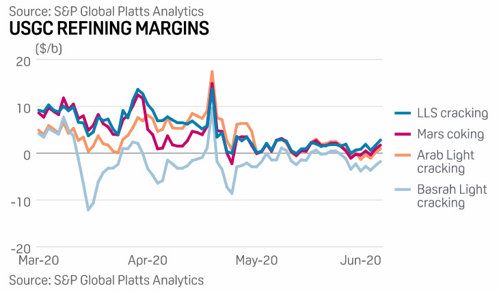

The world is rapidly changing. Political whiplash, the global pandemic, new technologies and evolving fuel standards are upending process industries and giving many CEOs a deep sense of unease. During the past year, when 5% of U.S. refining capacity was up for sale, refining margins were steadily falling (FIG. 1). According to Raymond James, global refinery capacity closures stood at 2 MMbpd, 60% of which were in the U.S.

FIG. 1. US Gulf Coast refining margins—Spring 2020.

This uncertainty poses a challenge for developing a successful business strategy, since the traditional approach assumes that the world is a stable and predictable place. It is not. Given our new levels of uncertainty, refinery CEOs are beginning to ask:

- How can industry apply traditional forecasting and analysis that are at the heart of strategic planning when the market is so unpredictable?

- How does one isolate the right signals to understand and harness change when we are already overwhelmed with information?

- How can our 1-year or 5-year planning cycles stay relevant when change is so rapid?

Sustainable competitive advantage no longer arises from the static attributes of position, scale and production, but from second-order capabilities that foster rapid adaptation. Rather than being satisfied with doing things well, successful companies must become very adept at doing things better.

Companies that thrive in the changing marketplace are quick to read and act upon signals of change. They experiment rapidly, frequently and economically with business models, processes and strategies. They manage complex multi-stakeholder systems in an interconnected world, and they empower their greatest resources: their workers.

Reading and acting on signals. For a company to adapt, it must be attuned to signals of change within the marketplace. Decoding these signals using advanced data-mining technologies and artificial intelligence (AI) to recognize relevant patterns enables companies to act quickly to refine or reinvent their business models. However, this comes at a cost. Only a very small percentage of the process industry has the resources to monitor, interpret and act on these signals. Still, many process facilities are leveraging their internal signal-reading capabilities to make operational interventions in real time, bypassing slow-moving decision hierarchies. According to Deena Zaidi’s “The role of data analytics in the oil industry,” those companies that used sophisticated process data and worker communication systems to acquire real-time business information improved their production by 6%–8%.

Experimentation. All companies use experimentation to develop and test new products, services and operations, but the real world is an expensive medium for experimentation. Traditional approaches can be costly and time-consuming and can, in some cases, saddle the organization with an unreasonable burden of complexity.

A growing number of adaptive competitors are using an array of new approaches and technologies—especially in virtual environments [digital twin, virtual reality (VR)/augmented reality (AR)]—to generate, test and replicate a larger number of innovative ideas faster, at lower cost and with less risk than their rivals.

Companies must broaden the scope of their experimentation. Traditionally, the focus has been on products and services, but in an increasingly turbulent environment, business models, strategies and even operations can also become quickly and unpredictably obsolete. Adaptive companies, therefore, use experimentation far more broadly than their rivals do.

Finally, since experimentation comes with failure, adaptive companies become failure tolerant, even to the point of celebrating it.

Manage complex multi-company systems. Signal detection and experimentation require a company to think externally and work more efficiently with its customers and service providers. This flies somewhat in the face of the belief that the unit of analysis for creating strategy is the individual process facility.

With an increasing amount of economic activity occurring outside corporate boundaries—such as outsourcing, offshoring, value nets and value ecosystems—it is important to develop strategies not just for individual companies, but also for dynamic business systems. Increasingly, the process industry is better viewed as a competing ecosystem of codependent companies than as a handful of competitors producing similar goods and working on a purely transactional basis with their customers and service providers.

Those companies that can create effective strategies at the network or system level will have an advantage. Adaptive companies learn how to integrate owner-service provider relationships and reduce their costs through alignment. They design and evolve strategies that include wider networks without having to rely on strong control mechanisms.

The ability to mobilize. Organizations must foster environments that encourage the knowledge flow, diversity, autonomy, risk-taking, sharing and flexibility in which adaptation thrives. Contrary to classical strategic thinking, strategy follows organization in adaptive companies.

A flexible structure and decentralizing decision-making are powerful levers for increasing adaptability. Adaptive companies replace permanent data silos and functions with independent teams that openly communicate and recombine according to need. This drives decision-making down from the board room to the boiler room, enabling the people most likely to detect changes in the environment to respond quickly and proactively.

Creating decentralized organizational structures destroys the one big advantage of a rigid hierarchy, which is that everyone knows exactly what they should be doing. An adaptive organization succeeds when it provides people with simple generative rules and the needed enterprise-level tools to facilitate clear worker-to-worker communication. This helps people make tradeoffs, and sets the boundaries within which they can make the right decisions.

The challenge. Adapting to change can be difficult for established process industries with hierarchical structures and fixed routines that have been oriented on managing scale and efficiency. Such systems die hard, especially when they were previously so successful.

Several tactics have provided adaptive advantages even in established companies. These create a context in which adaption can thrive. If you are the CEO of a process industry that needs to be more adaptive, challenge your team to:

- Identify the disruptors—Fast-changing industries are characterized by the presence of mavericks that often appear as entirely new players from different sectors. Ask your team to look at what they are doing and develop methods to protect your company against this new competition. They should look at what is happening in adjacent industries and ask, “What if that happened here?” While pattern recognition is always challenging in rapidly changing environments, it provides a tremendous competitive value.

- Identify uncertainties—Examine risks and uncertainties to understand how they could potentially affect your company. This simple extension of the familiar long-range strategy exercise forces people to identify and address what they do not yet know. Your organization must distinguish “false knowns” (questionable assumptions) from “underexploited knowns” (megatrends you may have acted on without sufficient emphasis) and “unknown unknowns” (uncertainties that can only be addressed by hedging). Once you identify these, address them.

- Examine alternatives—In a stable business environment, it is sufficient to improve what already exists and propose changes. The simple step of requiring that every change proposal be accompanied by several alternatives not only generates a more varied and powerful set of moves, but also legitimizes and fosters cognitive diversity and organizational flexibility.

- Incentivize risks—With a couple of simple enhancements, your portfolio of strategic initiatives can become the engine that drives your organization into adaptability. Every significant source of uncertainty should be addressed with an initiative. Depending on the nature of the uncertainty, the goal of the initiative can be as simple as responding to a neglected business trend, creating options for responding to it down the line, or simply learning more about it. In managing these initiatives, your company should be as disciplined with metrics, time frames and responsibilities as it would be with the product portfolio or the operating plan.

- Accelerate change—How fast a company adapts is a function of its decision-making cycle. Companies must accelerate change by making their planning processes more agile, more frequent and sometimes even continual.

Taking an active adaptive approach to change does not guarantee an immediate solution or remedy. Because our industry is facing uncertainty in rapidly changing times, you need a dynamic and sustainable way to stay ahead. Survival depends upon building an organization that exploits the capabilities behind what we think of as adaptive advantage.

About the authors:

ROGAN JONES is Vice President of Sales and Co-founder of AIS Software in Bellingham, Washington. He graduated with a BS degree from California Polytechnic Institute (Cal Poly) in Pomona and has spent the last 27 years in the oil and gas industry. Jones has extensive coding and programming experience across multiple industries, and has consulted with numerous clients throughout the world to improve operations management.

RICK KAISER is a licensed Professional Engineer with 30 years of experience in the oil and gas industry. He has extensive upstream and downstream experience as an automation engineer in the oilfields of northern Alaska and as a mechanical engineer at refineries in Washington State. Kaiser works at AIS Software in Bellingham, Washington as a Product Manager for software solutions used at oil, gas and petrochemical facilities around the world.

Comments