January 2026

Special Focus—Sustainability and the Energy Transition

Lessons learned from FCC biofeed coprocessing

In the global effort to decrease greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, the private transportation sector plays a prominent role. Lower carbon intensity fuels are important factors to enable a reduction in GHG emissions associated with transportation fuels. The use of existing assets in crude oil refineries can accelerate decarbonization or defossilization efforts, derisking uncertainty with large financing requirements and scaleup risks associated with new processes. As such, coprocessing of bio-derived feedstock in crude oil refineries will support the transition to lower carbon intensity fuels, chemical feedstocks and consumer products.

For more than 80 yrs, the fluid catalytic cracking (FCC) process has proven its adaptability, robustness and value in modern crude oil refining.1 The multitude of operating modes and refinery-specific economics around the FCC unit (FCCU) is a testimony to its flexibility. For example, while some refiners focus FCC operations on upgrading feeds to petrochemical feedstock such as propylene, others might operate their unit to maximize middle distillates or realize strong economics around the FCC bottoms product. In all these scenarios, the complete yield pattern is valorized with refinery-specific product economics.

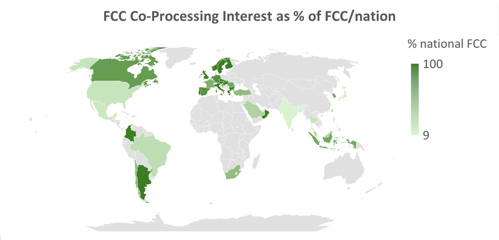

A large portion of refining companies are interested in coprocessing unconventional feedstocks in the FCCU, as shown in FIG. 1. Such feed streams can be biomass- or chemical recycling-derived liquids, which can be substantially different from crude oil-derived intermediates.

FIG. 1. The authors’ company’s visibility of interest in FCC coprocessing in percentage of FCCUs per nation.

Biomass-derived feed streams are commonly quite different from crude oil fractions. The class of these liquids spans a heterogeneous chemistry unified by the presence of oxygen as a major or minor component. For FCC operations with conventional feeds, oxygen can be introduced into the riser via entrainment of molecular oxygen carried over from the regenerator, along with the circulating catalyst. Oxygen is typically present in trace concentrations in crude oil-derived streams. Oxygen is present in much higher concentrations in the case of unconventional feeds, and this can cause new processing and specification challenges in refineries.

Conversely, liquids from waste streams like mixed plastic waste, municipal solid waste, sewage sludge or waste (end-of-life) tires present a heterogeneous feed class with respect to chemistry and the presence of trace contaminants. Challenges and opportunities continue to be monitored in the industry with the increasing availability and processing of these feeds.

With increasing interest in coprocessing unconventional feedstocks, several FCCUs around the world have trialed and/or implemented continuous coprocessing, despite a lack of certainty in regulatory support. The authors’ company’s technical service team receives many inquiries regarding the opportunities and challenges that come with coprocessing, trying to avoid problems that others experienced while generating added value from coprocessing. This article discusses observations, opportunities and challenges from FCC coprocessing of biomass-derived feeds and provides insights from commercial applications and pilot plant evaluations.

Feedstock. Globally, the types of bio-derived feedstocks vary from so-called fats, oils and greases (FOGs, often also described as lipids) like seed oils, animal fats and waste (used) cooking oils to lignocellulosic streams like wood-derived pyrolysis oil and tall oil. Selection and supply of such feedstocks in refinery scale quantities are a challenge. Early movers in many cases secured supply by direct investment or joint ventures (JVs) with established market actors.

Edible oils or first-generation biofeeds are an important source of bio-derived feed streams in some regions. Miscibility and thermal stability are typically of lower concern with such streams. Second generation or “advanced” biofeeds—such as tallow/animal fats, waste cooking oils, etc.—typically vary from batch-to-batch to some extent. As a result, increased monitoring is required to mitigate the negative effects of contaminants or challenges associated with varying levels of oxygen. Regional regulatory requirements can make advanced biofeeds particularly attractive. For example, high demand for waste cooking oils has driven high prices and rapid supply chain development for those feeds. The FCC coprocessing route also competes with the hydroprocessing route [hydrotreated esters and fatty acids (HEFA)] to produce renewable diesel or sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), further increasing demand for these feeds.

Much of the supply of lipids stems from specific regions. Asia, for example, is a large supplier of edible oils and waste cooking oil. Trade flows of these feeds drive local availability. This underscores the need to secure feedstock supply at an early stage. For example, the investments in renewable diesel plants in the U.S. that accompanied favorable investment incentives of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) drove a significant volume of waste cooking oil supply from Asia towards North America.2

While FOGs are limited in quantity and are often directed to the HEFA processing route, lignocellulosic feed streams like bio-derived pyrolysis oil are challenging to process. Overcoming these processing challenges will be important to open the lignocellulosic value chain to more investment and, consequently, widen availability, as the supply of FOGs to refinery value chains is predicted to be limited.

As the FCC process is redistributing hydrogen in feed to products, feed hydrogen content is an important property to assess crackability and product tendencies of FCC feedstocks. When heteroatom content is significant, it must be considered instead of focusing on pure hydrogen-to-carbon (H/C) ratio. Chen, et al.3 introduced the concept of effective hydrogen index (EHI), with lignocellulosic feeds having a low EHI (FIG. 2). This reflects the hydrogen deficiency of such lignocellulosic feeds, indicating lower crackability and lower H/C incremental yield.

FIG. 2. EHI3 vs. feed oxygen content of a selection of different bio-derived feeds.

Supply chain logistics represent the first challenge to consider in the assessment of coprocessing opportunities. The selection of a particular feedstock and securing supply are important starting points for projects. The upstream logistics of unconventional feedstocks are important items to consider and are typically associated with some investment. Feedstock segregation is typically required. The properties of the selected feedstocks in terms of miscibility, interaction with the other components of combined FCC feed and thermal stability govern considerations about injection points into the feed line to the FCCU. While typically unconventional feedstock-type options can be considered separately, the processing of several unconventional feedstocks should include investigations into the interactions among them. Anecdotal evidence indicates the potential for negative interactions between different biofeeds that could result in operational difficulties.

All bio-derived liquids have the commonality of introducing a new heteroatom (oxygen) in significant concentration to the FCCU. The FCC process is effective in deoxygenating the biogenic compounds without the consumption of previous added hydrogen, especially considering FOGs. The oxygen in such feeds is almost completely converted to water, carbon monoxide (CO) and carbon dioxide (CO2) (see yield section).

In addition to oxygen, bio-derived streams can contain contaminants like alkali and alkaline earth elements and phosphorus. While some of these contaminants are well understood due to their presence in traditional feedstocks, others pose new challenges to FCC operation [refer to the equilibrium catalyst (Ecat) contaminant section for more information]. Catalyst contaminants and deactivation do not appear to be a predominant constraint observed commercially at current low- to moderate-coprocessing rates. As coprocessing rates continue to increase and feedstocks with higher contaminant levels are evaluated, catalyst deactivation must be addressed. The development of metals-tolerant catalyst technology and feed treatment options will be an active area of research.

Another concern with the properties of bio-derived liquids is often associated with their increased acidity or elevated chloride content. Most of the concern is concentrated around the hardware upstream of the FCCU’s riser with regards to the acidity. Corrosion must be assessed and monitored in detail during the assessment of coprocessing projects.4 Known effects of increased chloride content of unconventional feeds are discussed below.

Some of the bio-derived feedstocks, especially bio-derived pyrolysis oils, might not be thermally stable and therefore require the bypassing of the FCCU's preheat train, including separate feed injections. FCC licensors offer technical solutions for such feedstocks.

The water content of the bio-derived feedstocks could be high. Free water should be removed upstream from the feed injectors to prevent uncontrolled water vaporization, leading to riser vibration or feed nozzle damage. For example, a feed drum with a water boot will reduce the risk of free water entrainment.

Riser/reactor section: Heat balance effects from lower heat of reaction. The exothermic formation of CO, CO2 and water will reduce the overall endothermic heat of reaction when coprocessing renewable FCC feedstocks.

Bryden, et al. described a ~15% lower endothermic heat of reaction from 100% soybean oil processing relative to cracking vacuum gasoil (VGO) in a Davison Circulating Riser (DCR™) pilot plant.7 The FCC heat balance responds to the lower heat of reaction by requiring a lower catalyst-to-oil (cat/oil) ratio to maintain the same riser outlet temperature (ROT), thereby reducing coke yield. Many units limited by catalyst circulation and/or air blower capacity may alleviate that constraint by replacing some traditional feedstock with a renewable bio-based feedstock. Reduced cat/oil ratio and coke demand results in a lower conversion of the base feedstock. This can be offset by increasing ROT or Ecat activity.

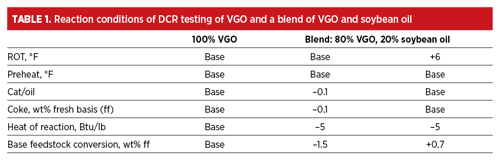

For example, the heat balance effects associated with coprocessing 20% soybean oil allows the ROT to be raised at a constant air blower and catalyst circulation capacity, resulting in a gain in conversion of the base feedstock, as demonstrated in a pilot study (TABLE 1).

Lower flue gas opacity. Some refiners processing pyrolysis oil in FCCUs observed a decrease in flue gas opacity, alongside an increase in slurry ash content. During the cracking of pyrolysis oil in the FCCU, biochar—a solid, carbon-rich byproduct of thermochemical biomass conversion—can form. Froehle, et al.8 explain that biochar within the FCCU reactor has alkali metal properties, which enable it to attract catalyst fines. Due to its low density compared to FCC catalysts, biochar and the attached catalyst fines are more likely to be lost from the reactor, leading to a higher concentration of catalyst fines in the slurry product. The lower flue gas opacity observed was attributed to the reduced presence of catalyst fines in the regenerator. Increased slurry solids content may require additional monitoring and mitigation from equipment reliability and finished product property perspectives.

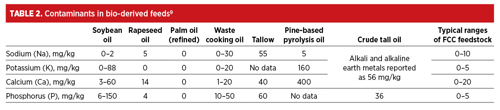

Catalyst inventory. As mentioned above, bio-derived feedstocks will introduce known or new catalyst poisons and inhibitors into the FCCU. These contaminants include alkali and alkaline earth elements and phosphorus (TABLE 2).

Alkali and alkaline earth elements are known to be FCC catalyst poisons. Zeolite deactivation is the consequence of increasing the concentration of alkali elements, while alkaline earth elements like Ca are known to exhibit pore mouth blocking effects.10 Phosphorus, while currently hardly present in fossil FCC feedstocks, is expected to be introduced by biofeed coprocessing, and research indicates that this also contributes to pore mouth plugging.

These contaminants provide new challenges for catalyst technology companies to address through the development of enhanced contaminant-tolerant technology and traps. Effective management of these contaminants can be achieved with the use of advanced adsorbents (e.g., the authors’ company’s proprietary silicaa), which is employed extensively for the purification of lipid feedstocks in the edible oil industry.11

Biofeeds, such as waste cooking oils, can also contain mg/kg levels of chlorine as a contaminant. This can contribute to a corresponding increase in the chloride content in the sour water stream and cause an adverse impact.

Yield structure and downstream considerations. The FCC catalyst and the process provide high activity for oxygen removal. Commercial observations and extensive pilot plant evaluation studies provide significant insight on the deoxygenation reaction pathways in the FCC process while coprocessing biofeeds. Most of the feed oxygen is converted to water, CO and CO2, with the remaining oxygen resulting in trace (mg/kg) levels of organic oxygenates present in gas, liquid product and sour water streams. While small amounts of oxygen-containing products can be formed during the processing of conventional petroleum feedstocks, the concentration of oxygen-containing products greatly increases while processing biofeed.

The yield structure impact of coprocessing bio-derived feed streams cannot be generalized apart from the increased yields of water, CO and CO2. As such, the amount of the biofeed coprocessed contributes to the sellable product pool based on the rate minus oxygen in feed, coke and dry gas yields. Some biogenic carbon is lost from the product pool via the conversion of oxygen to CO and CO2. With lipidic feedstocks, nearly all oxygen is converted to water and carbon oxides (COx) (CO and CO2), and the product distribution is about 80:10:10 for water, CO and CO2, respectively, with trace levels of oxygenate byproducts present in liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), cracked naphtha and heavier liquid streams.

Other biogenic feedstock types might show a different pattern. In FCC process monitoring, it is important to consider the mass balance impact of increased water yield and the higher CO and CO2 levels in sponge gas to reflect the FCC yield pattern accurately. Accurate quantification of water yield is complicated by the multiple steam injections and entry points in the unit and downstream operation. Additionally, a low coprocessing rate relative to fossil feed complicates an accurate quantification of additional sour water production and COx in sponge gas.

Although water is generated by a reaction of oxygenates, the overall sour water increase can be worsened by the direct introduction of water from the coprocessed feed. Some alternative feeds may contain significant amounts of water, either from production or contamination during logistic operations. For example, some biomass-based pyrolysis oils have been observed to contain water up to 25 wt%.

FCC is often referred to as carbon rejection process but could also be defined as a hydrogen redistribution process. The hydrogen content of the FCCU feed is redistributed among the products of the cracking process, with the unconverted product [light cycle oil (LCO) and bottoms] and coke having lower hydrogen content, while the gaseous products and cracked naphtha are higher in hydrogen content. As such, the formation of water from the oxygen in the biofeed adds to the consumption of hydrogen. Pilot plant testing shows a respective lower hydrogen yield for the coprocessing of biofeeds.12

Other yield pattern impacts are dependent on a multitude of factors like biogenic feedstock type and quality, base fossil feed quality, unit operation, catalyst and additives. Exemplary data have been shared in publications.12,13

TABLE 3 summarizes yield data from a DCR pilot plant study for the coprocessing of canola oil, with VGO as a reference fossil feed and a typical Ecat. This study showed the blending of canola oil with VGO caused a slightly higher propylene yield, slightly lower C4= and gasoline yield, higher LCO yield and a significantly lower bottoms yield. As expected, COx and water yield increased with canola oil content.

In addition to the yield structure impact, the distribution of the biogenic carbon content to the final products might have a governing impact on the FCCU’s coprocessing economics. Determining the biogenic carbon content by ASTM D6866 enables the assessment of biogenic carbon distribution in FCCU products, including sponge and flue gas. Depending on the regulatory framework, such testing might be required to generate value from FCC coprocessing.

In the case of low coprocessing rates, the quantification of yield effects and biogenic carbon distribution may be within the variability of normal FCCU operation.

Pilot plant studies routinely incorporate the evaluation of key product properties such as naphtha sulfur and octane. The starting quality of the FCCU’s base feed is also important when evaluating the impact on both yield structure and product quality. For FCCUs processing a deeply hydrotreated feedstock, there could be an increase in the portion of sulfur ending up in the gasoline range. Also, at significant biofeed amounts in the feed (> 15%), sulfur in the gasoline fraction may increase, whereas at very high levels, the effect of dilution with zero-to-low sulfur biofeeds will be the dominating factor. Pilot studies and field observations also have shown that at appreciable biofeed coprocessing levels, carbonyl sulfide (COS) can be formed due to the reaction of COx with H2S. This will lead to COS enrichment in the propylene stream. These observations indicate the effect of biofeed coprocessing on total sulfur distribution among FCC products.

Increased reactor side CO and CO2 are the most likely to impact the FCCU's operation through increased load on the wet gas compressor, as well as higher vapor traffic in the absorber tower and to the dry gas amine scrubber. Generated from the authors’ company’s DCR pilot plant data coprocessing 20% canola oil with a gasoil base feedstock, FIG. 3 demonstrates the expected magnitude of increased CO and CO2 from the oxygen in the feed.

FIG. 3. Oxygen balance from DCR testing of a VGO and canola oil blend (80:20).

For units operating at wet gas compressor limitations or coprocessing significant percentages of oxygen-containing feedstock, the increase in non-condensable gases can cause wet gas compressor bottlenecks and reduced profitability due to a need to reduce conversion to accommodate the incremental compressor load. Examining operation downstream of the wet gas compressor yields similar conclusions with increased vapor traffic in the absorber tower and amine treating of the FCC dry gas.

Additionally, CO and CO2 pose challenges to units downstream of the FCCU, including amine capacity to adsorb H2S and fuel gas system limitations. The primary purpose of treating the FCC dry gas (ethane and lighter) is the removal of H2S prior to routing the stream to refinery fuel gas. The solvents used for this dry gas sweetening are selective toward adsorbing H2S as well as CO and CO2.15 This presents additional challenges for sweetening the dry gas, which may require increased amine circulation rates and larger ancillary equipment, as well as diminished operation of the sulfur recovery unit.16 There are different types of amines with or without CO/CO2 adsorption. It is possible to selectively remove COS/CO/CO2 from the dry gas, but it requires changing the amine type and potentially redesigning the amine regeneration unit.

CO and CO2 that are not captured in the amine scrubber enter the refinery fuel gas system, resulting in a lower heat of combustion. This lower heat of combustion may have significant impacts to refining operations if there are furnaces operating at burner tip pressure limits. This may result in a wide range of consequences, including lower unit throughput or recovery, incremental natural gas purchases, or the need to vaporize and fuel propane to deliver incremental heat of combustion to the refinery fuel mix.

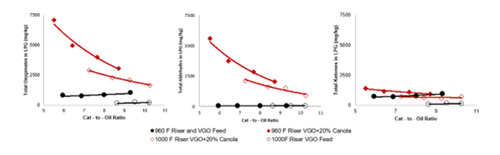

In LPG products (C3s and C4s), the authors’ company and refiners have observed increased oxygenates, with the primary species comprising of aldehydes and ketones, especially when coprocessing lipidic feedstocks. FIG. 4 shows that coprocessing 20% canola oil in the DCR results in a substantial increase in total LPG oxygenates.

FIG. 4. LPG oxygenates yields comparing VGO and VGO/canola oil feedstocks in a DCR.

This pilot plant study demonstrated that aldehydes increase more than ketones. In addition, aldehydes have a stronger correlation to FCC severity, with the cat-to-oil ratio influencing aldehydes to a greater degree than reactor temperature. Additionally, it is important to note that aldehydes are not typically observed in FCC products in appreciable amounts without coprocessing oxygen-containing feedstock. So, not only does oxygenate content increase, but there is also the introduction of a compound that is not widely encountered in normal FCCU operations.

In the LPG product treatment section, oxygenates are thought to play a major role in foaming, emulsion formation and fouling in caustic treater and amine systems. In other industries (including ethylene plants), aldehydes are well documented as the cause of “red oil” formation. Red oil forms as the result of an aldol condensation reaction catalyzed by a base, where oxygenate species react and form a heavy reddish oil.17 This red oil can result in fouling or emulsions in the treater systems and has been observed in coprocessing FCCUs.

FCC product oxygenates in LPG and naphtha can also cause issues downstream of the amine and caustic product treatment sections. Any oxygenates that are not removed in these washing steps will end up in the feed to various C3= and C4= processing units, including cumene, polygasoline, methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE)/ethyl tertiary-butyl ether (ETBE) and alkylation units. In alkylation units, oxygenates, such as acetone, result in water formation and the increased formation of acid soluble oils, ultimately resulting in higher acid consumption.18 In some cases, the reaction of side products in downstream conversion processes may result in higher boiling range sulfur molecules and impact gasoline pool blending. Unlike alkylation, where increased acid consumption may be relatively straight forward to handle, conversion processes using fixed-bed catalysts present acute pain points during coprocessing activities.

A common area of contact with a basic medium is in mercaptan extraction and/or sweetening units, which are common for reducing sulfur in both LPG and naphtha streams. Because organic oxygenates can absorb into an aqueous phase and react under basic conditions, there is potential for the accumulation of atypical species in the caustic streams, and the routing of spent caustic is an important issue to consider. The disposal of this caustic can become difficult and expensive, especially for refiners without any neutralization facilities. Caution is necessary when this spent caustic is routed elsewhere within the refinery, as combinations of conditions can result in fouling from red oils.17 Furthermore, the presence of phenols or a higher tendency to form stable emulsions can result in increased carryover of aqueous phases, resulting in hazy naphtha and increased tank draining requirements.

As mentioned in the yield structure section, elevated concentrations of COS can impact the propylene stream quality and poison the catalysts downstream of the FCCU.

As discussed above, there is significant potential for increased sour water rates due to the generation from oxygenates or direct introduction. With knowledge of the total water and oxygen content in the feed, it is possible to model the effect on sour water production. The pH of sour water should be monitored and remain in the typical range (8 pH–9 pH) to avoid corrosion, as the stream will contain higher amounts of phenols and organic acids.

Coprocessed feeds can also include chloride, sometimes in high concentrations. Chloride directly entering the riser reactor has the potential to cause salt deposits in the main fractionator and its overheads system,19 increasing the importance of effective washing (and, therefore, further increasing sour water loads).

When coprocessing oxygen-containing feeds in the FCCU, it is critical to assess the routing of sour water in the refinery. Some refiners route the FCCU’s stripped sour water to crude desalters, which under typical conditions will drive phenols into the oil phase and reduce the load on the wastewater treatment plant (WWTP). This option can present environmental challenges if there is a crude unit outage. Other refiners route stripped sour water directly to the WWTP, which typically incorporates a biological treatment plant. For some refiners, this is acceptable, as the WWTP can tolerate and remove moderate levels of organic oxygenates, such as phenols, to meet environmental obligations. However, this can be a difficult constraint for some refiners, especially during winter months when colder temperatures affect the microbial activity of the biological treatment plant.

The presence of low levels of oxygenates and reactive species in product streams and sour water impacts have the potential to cause significant challenges. Beyond the immediate FCC impacts, preparation of lab facilities and affected downstream processes are critical to successful commercial coprocessing trials and applications. Lead times for specialized analytical equipment and calibration standards can be long, and the importance of establishing pretrial baselines should not be underestimated when planning project timelines. In the case of analytical data collection, the location of sample points within the process are important to assess. Product treatment steps may impact the concentration of components of interest. For example, collecting oxygenate samples after a water washing step could indicate a much lower concentration than actual.

Takeaways. There is substantial interest in the refining industry in coprocessing bio-derived feed streams in the FCCU to produce lower carbon intensity products. With the flexibility and robustness of the FCCU, coprocessing low amounts of biogenic feedstocks is possible with limited impact and capital investment. A significant number of FCCUs globally have performed commercial trials, and some have converted to continuous operation.

This article has provided a high-level overview of the lessons learned from biofeed coprocessing to enable an enhanced understanding of the required preparation and monitoring activities in FCCU biofeed coprocessing.

NOTE

a W. R. Grace’s TRISYL® Silica

LITERATURE CITED

1 Letzsch, W. and C. Dean, “How to make anything in a catalytic cracker,” AFPM Annual Meeting, Orlando, Florida, 2014.

2 Wood Mackenzie, “The role of biofuels in the decarbonization of transport,” April 2024.

3 Chen, N. Y., D. E. Walsh and L. R. Koenig, “Fluidized-bed upgrading of wood pyrolysis liquids and related compounds,” ACS Symposium Series, September 30, 1988, online: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/bk-1988-0376.ch024

4 Fazackerley, W., “Managing corrosion risk in SAF and renewable diesel processes,” Decarbonisation Technologies, February 2025.

5 Shell Catalysts & Technologies, “Shell FCC co-processing nozzle,” FCC technology portfolio factsheet.

6 Golczynski, S., et al., “Tackle operational challenges with FCC coprocessing applications,” Hydrocarbon Processing, May 2024.

7 Bryden, K., et al., “Flexible pilot plant technology for evaluation of unconventional feedstocks and processes,” Catalagram, No. 113, 2013.

8 Froehle, D., et al., “Methods of reducing flue gas emission from Fluid catalytic cracking unit regenerators,” United States Patent US 10,246,645, 2019.

9 Bailey, R., et al., “Supporting refinery sustainability goals through the renewable feedstock value chain,” Catalagram, No. 126, 2021.

10 W. R. Grace, Catalagram, No. 121, 2018.

11 W. R. Grace, “Biomass-based diesel: TRISYL silicas for biodiesel and renewable diesel feedstock pretreatment,” online: https://grace.com/industries/biofuels/biomass-based-diesel/

12 Fernandez, A., et al., “Defossilizing the FCC unit via co-processing of biogenic feedstocks: From laboratory to commercial scale,” Catalagram, No. 128, 2023.

13 Perez, E., et al., “Decarbonize the FCCU through maximizing low-carbon propylene,” Hydrocarbon Processing, March 2024.

14 Harding, R. H., et al., “Fluid catalytic cracking selectivities of gas oil boiling point and hydrocarbon fractions,” Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, 1996.

15 Bullin, J. A. and J. Polasek, “Selective absorption using amines,” Bryan Research and Engineering Inc. Technical Papers, 2006, online: https://www.bre.com/PDF/Selective-Absorption-Using-Amines.pdf

16 Selim, H., A. K. Gupta and A. Al Shoaibi, “Effect of CO2 and N2 concentration in acid gas stream on H2S combustion,” Applied Energy, October 2012.

17 Cuoq, F., et al., “Red-oils in ethylene plants: Formation mechanisms, structure and emulsifying properties,” Applied Petrochemical Research, 2016.

18 AFPM, “Question 32: What are the impacts of the presence of acetone in the alkylation unit feed? How is this formed in the FCC? Comment on both HF and sulfuric units,” AFPM Q&A, 2012, online: https://www.afpm.org/data-reports/technical-papers/qa-search/question-32-what-are-impacts-presence-acetone-alkylation#:~:text=Typical%20acetone%20concentrations%20in%20the,as%20the%20acid%20strength%20falls

19 Melin, M., et al., “Salt deposition in FCC gas concentration units”, Catalagram, No. 107, 2010.

Comments