West African push to clean up toxic fuel hits snags

LONDON (Reuters) -- A West African drive to clean up toxic fuels that campaigners say pose a health hazard to millions has run into difficulties less than two months after it was announced, according to importers, traders and other oil industry insiders.

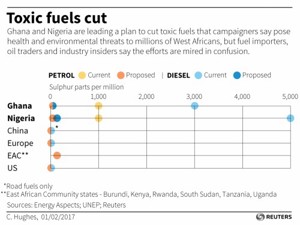

Late last year, Nigeria, Ghana, Benin, Togo and Ivory Coast unveiled a plan to reduce the amount of poisonous sulfur they would allow in fuel.

But the announcement, under the auspices of the United Nations Environment Program, did not give full details of the changes or when they would come into force. That has caused uncertainty, particularly in Nigeria and Ghana, which consume more than half of the fuel used in the region.

Ghana has issued guidance and invited public comment on the fuel quality it wants. But political sources told Reuters that a recent change in government could delay new rules.

Nigeria is still drafting its own rules. Fuel suppliers who bid for 2017 contracts do not know the quality of fuel they will have to import.

"Follow-on detail has been conspicuously sparse, leaving the market effectively in no man's land," said James McCullagh, an analyst with Energy Aspects in London.

A source at a fuel importing company added: "It's ridiculous. You can't expect us to bid for a contract if we're going to suddenly have to supply a totally different fuel."

AIR QUALITY

Tightening the law is crucial to improving air quality in West Africa, where 335 million people use fuel that has a sulfur content many times above what is legal in Europe and the United States.

Sulfur is the target because of its recognized impact on respiratory health, and the acute danger in traffic-clogged cities like Lagos or Accra. There is a plentiful supply of low-sulfur fuel on international markets, and widely available refinery technology that can strip transport fuel of sulfur.

UNEP, the African Refiners Association (ARA), and health campaigners have been pressing governments for years to improve fuel quality.

The issue was highlighted in September, when Public Eye, a Swiss campaign group, said international trading companies were using West Africa as a dumping ground for high-sulfur fuels.

UNEP program officer Jane Akumu said Public Eye's report had helped fast-track improvements in fuel quality that had been under consideration for a decade.

Legal changes and regulatory enforcement will be needed if the trade in high-sulfur fuels to the region is to be curbed, industry experts said.

In Nigeria, dozens of traders and local importers compete to supply fuel and the lowest bidder usually wins, making it hard to market high-quality fuel of the kind used elsewhere.

Ghana last week published proposals, still not finalized, for a limit of 50 parts per million (ppm) of sulfur content in both gasoline and diesel sold at the nation's pumps.

Nigeria's proposals, also not finalized, would cut the sulfur level on imports from 1,000 to 150 ppm for gasoline, and from 5,000 to 500 ppm for diesel. The Nigerian National Petroleum Company (NNPC), said its three domestic refineries would be exempt until at least 2020.

The aim is to publish draft changes in March, although this year's tenders to swap imported fuel for crude oil were set to close on Feb. 2. Because Nigeria is short of dollars, such swap deals account for the bulk of its fuel imports.

In the meantime, officials at government ministries and the NNPC would not confirm the new sulfur levels. And to add to the confusion, some of those bidding for the fuel swap deals said they understood the limits to be 50 ppm for gasoline and a much-higher 500 ppm for distillates.

Spokesman Ndu Ughamadu said the NNPC it was "working towards meeting improved fuel quality standards alongside the trade and environment ministries."

SENSIBLE, BUT EXPENSIVE

David Bleasdale, executive director of CITAC, a consultancy that works closely with the ARA, said the changes are sensible and "what civil society expected to reduce urban pollution".

But he said cost would be substantial. Traders said the proposals would cost at least $10-15 per tonne, or more than $250,000 for each cargo of gasoline.

"Behind it all, there is a real dollar shortage in Nigeria, so the government needs to clarify its priorities," Bleasdale said.

Nigeria's environment minister, Amina Mohammed, the force behind the regional campaign, will leave the ministry soon to take up a senior post at the United Nations, a potential setback for efforts to reduce sulfur.

But Akumu of UNEP said the governments had already agreed, and the only question was implementing the changes.

"It was costing them in terms of health," Akumu said. "It's a priority."

REFINERIES AND ENFORCEMENT

The proposals will heap costs on West African oil refineries. None of NNPC's facilities produce enough of the high-quality fuels needed, nor do Ghana's state-run Tema Oil Refinery or Ivory Coast's Société Ivoirienne de Raffinage.

For Nigeria, Ughamadu said upgrades were underway at the Port Harcourt refinery, and planned at Kaduna and Warri, where installing equipment to cut sulfur levels could cost millions.

There are other costs too. Rolake Akinkugbe, head of energy and natural resources at FBN Bank, said up to 20% of Nigeria's oil product imports were smuggled to neighboring countries, so if new fuel standards are to work, it will require regional cooperation and tough enforcement.

"The cost of doing so may be prohibitive," Akinkugbe said.

Reporting by Libby George and Matthew Mpoke Bigg; editing by Giles Elgood

Comments